The Quiet American: Brüpond and the birth of modern London beer

I only met David Brassfield once, at The Kernel on a warm day at the end of July 2012. He was standing patiently in front of a fermenting vessel, a notepad clutched to his chest, waiting to speak to Evin O'Riordain. I noted how smartly turned-out he was: he was wearing modish thick-rimmed spectacle, as I recall, and there was a biro tucked into the breast pocket of his white shirt.

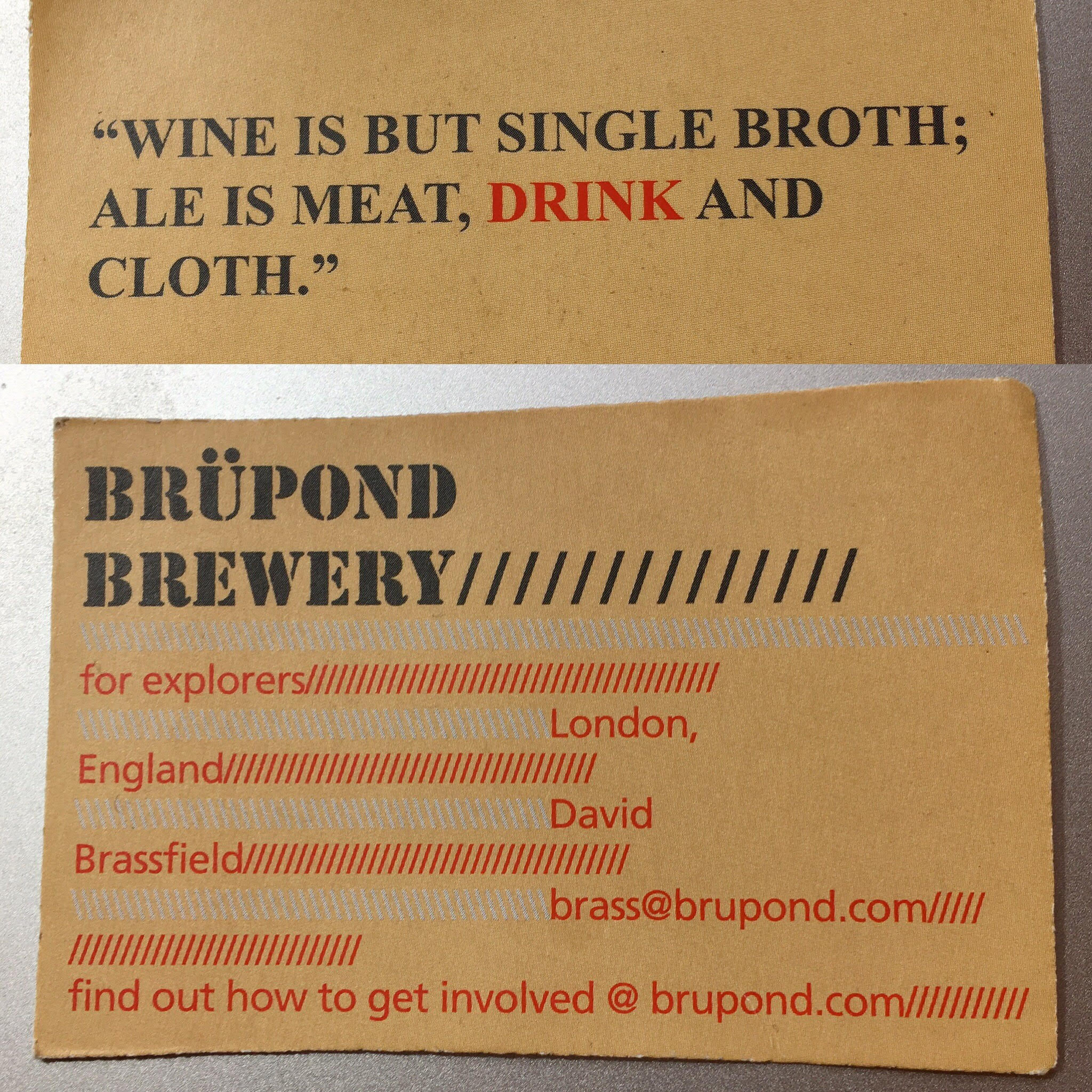

For a moment I imagined him as an American journalist, here to find out more about London's brewing renaissance. A quick chat dispelled that notion. He was setting up a brewery in London, he told me in easy-going Midwestern style, and gave me his card: Brüpond Brewery, it read in thick black type, “for explorers”. It listed his name and email address, but no phone number. On the back was a '16th-century English proverb': “Wine is but single broth; Ale is meat, drink and cloth.”

13 months later, Brüpond was up for sale.

It was intriguing. I emailed Brassfield to see if he'd like to speak about it. He was polite but non-committal; he'd just had a child, he said, so he was out of commission for a while. I emailed other brewers, who told me that Brüpond's beer was often substandard - but, I reasoned, that wasn't uncommon at the time.

I spoke to investors like Jan Rees, who put £500 into Brüpond: “I'm not really in to beer at all, but it was a great pitch and David came across as super confident & capable,” he told me over email - but also that, after this experience, “I would avoid the microbrewery sector completely because there are just way too many start-ups with no realistic hope of a decent investment return.” But I never heard back again from Brassfield.

Until a few weeks ago, when a message popped up on my email. It took me a few moments to register the name, but the message was unequivocal. “Hey Will! I know it's 4 years later... You still want to talk?”

I did. Back in 2013, this would have been an interesting tale of how an enthusiastic young American got out of his depth in London. Now, just five-and-a-half-years on, it feels like a time capsule, a reminder of an era that is gone for ever (even if there are plenty of evergreen lessons here for anyone planning to start a business, brewing or otherwise). London brewing has moved so fast; companies like Beavertown or Brew By Numbers, which were just starting out then, are well-established; others, like Gipsy Hill, weren't even founded until 2014.

These were the Wild West days of London beer, when quality was variable but it was all so exciting it didn't matter. (2013 was the year of London’s Brewing, perhaps the worst British beer festival in history and definitive proof that it is possible to misorganise a piss-up in a brewery). As the author of Craft Beer London, an app and book which is itself a period piece now, I was used to registering the opening of breweries, not closures. There were rumours that Brassfield had gone back to the US, that there were visa issues. So what really happened?

David Brassfield outside the Brüpond brewery in Leyton in 2013

“It was extremely stressful, occasionally depressing, and I had a son on the way,” Brassfield, now 34, tells me down the line from Chicago, where he works and lives with his wife and young family. “I needed to look after my family. I was working multiple 18-hour days in a row just to get all the beer ready, I was hand-capping 2000 bottles by myself, and that takes a while.

“I had been going for about a year-and-a-half and I reinvested every dime back into the brewery. I hadn't paid myself. My buddy, who was a friend from high school and just happened to have moved to London around the same time as me, was working for me, essentially, for free.”

For all that it was a deeply stressful time for Brassfield, though, he was onto something. In an era when British breweries raise millions of pounds through crowdfunding, his efforts - he raised £35,000 from 44 investors through Crowdcube, with another £30,000 coming from elsewhere - seem small-time. But he was ahead of the crowd (no pun intended). Few British breweries had done this before him. Brüpond, it would be fair to say, was a good idea executed badly.

“It was extremely stressful, occasionally depressing, and I had a son on the way”

“I had moved from Chicago to LA and then to London, and it seemed like in each of those cities there was a certain moment where you could see craft brewing taking off,” says Brassfield, who grew up in Colorado. “And in Chicago I think that really was in 2008, 2009 when you started to see craft brew appearing in bars rather than just Coors, Budweiser and Miller.

“And then we moved to LA in 2009 and the same thing was happening there. And then I moved to London, and again, it was right then and there. And right when we moved is when Crowdcube was being launched as well. So it just seemed like there was a bit of synergy going on within the brewing world, that it was a good time and a good place to start a brewery.”

“It just seemed like there was a bit of synergy going on within the brewing world, that it was a good time and a good place to start a brewery”

Given what's happened since, that's hard to deny. Whether Brassfield was the right man to open that brewery is open to question. He had been a homebrewer, he says, for five years, but had no professional experience. The Crowdcube pitch was very different from the all-bases-covered, 100-page efforts breweries put out now. The first paragraph gives a flavour of the overall tone:

“Brewing in London has a very long tradition going far beyond the Romans and written history. The Celtic tribes that once lived in the UK area used to brew psychedelic beer using very dangerous local plants. Over time, and through history, what has been brewed and drank has changed quite a bit; but, has been relatively stable over the last 100 years. UK breweries tend to focus on Bitters, Lagers and Real Ale [bold type from original document]. Generally these beers have a malty taste, floral hop aroma, and a dry crisp finish.”

Dravid Brassfield’s card, front and back, from the summer of 2012

But he was unlucky too. He hired a brewer, who helped him acquire a brewkit, only for that brewer to return home to South Africa after a family tragedy, just as they were starting to brew. That left him as the head brewer, a job he admits he never mastered. “I couldn't get that consistency to save my life, and to this day I don't know why,” he says. “I don't know if it was an equipment problem or if there was something else going on. I could never get it to work for me.”

Despite that key element of bad luck, though, there were plenty of mistakes. He gave up 25 per cent of the company for £35,000 - far too little, as he now readily admits. “The fact that it closed out in, I think it was like five days, no, it was not the right percentage,” he says. “To hit the nail on the head, you want the thing to last the entire 60 days. It was a bad valuation by me.”

He started with a chili porter, at a time when the most avant-garde London beer drinkers were still thrilled by hop varieties like Citra and Mosaic. Even now, many Londoners will struggle to name more than a couple of pepper varieties, but the beer was called Ain'cho Mum's Porter, a play on the Ancho pepper (which, naturally enough, you can now buy in Waitrose).

“Here in Chicago there's a brewery called Pipeworks and all they do is crazy beers,” he says. “They don't have a particular beer that is the go-to beer and then they have all this other fun stuff. So I guess that was kind of my idea. I wanted my beers to be a little bit different and not have your typical milds, your typical IPA. Looking back on it, I should have had an easy-going crowd pleaser, which I didn't. I should have focused on a session IPA.”

And then there was the site, in Leyton. “Our location sucked,” he says. “The second floor was all rented out by these Evangelical churches, and I didn't think twice about it. I didn't even think that was going to be an issue.

“Sometimes we made some of the best beer in London, and sometimes we made some of the worst beer in London”

“But when I went to get my on-premise sales license, there was a huge fight over it because they didn't want drinking to be occurring while they were worshipping. And they worshipped like four times a week! So it was this big fight for about ... It wasn’t really a fight. I mean everybody was calm and reasonable, but it took like four months to get my on-premise sales license. And that's where a lot of new breweries get their margin, being able to sell directly to customers.”

The first brew, in October 2012

All this might not have mattered had Brüpond make consistently good beer, but it didn't. Bloggers were quickly onto this: Justin Mason, one of the kindest people in the beer-blogging world, described Tip Top Hop, an IPA, of tasting like ‘soggy cardboard’. Matt Curtis, meanwhile, wrote that “I'm loathe to pour any beer away and I persevere with [Tip Top Hop] right to the very end and as it warms that fruity sweetness does come to the fore but not ever in the amount that I desire.”

“I stopped reading [online] commentary,” says Brassfield. “Sometimes people said it was great, other times people said it was horrible. It was very inconsistent. I think sometimes we legitimately made some of the best beer in London, and sometimes we legitimately made some of the worst beer in London.”

The investors didn’t always help, either. Crowdfunding is understandably popular with modern brewers, who see it as a way to raise much-needed funds without having to deal with the scrutiny and stipulations that come with going to a bank. It means your most committed, most pliant customers are providing your cashflow. It should make life easier, but that’s not how Brassfield found it.

“Our location sucked. The second floor was all rented out by these Evangelical churches, and I didn’t think twice about it. I didn’t even think that was going to be an issue”

“I was going around to these pubs, up to six pubs a night, meeting the managers, posting it on Facebook, on Twitter,” he says. “And one of the investors on Facebook was like, ‘Why don't you stop drinking all that beer and start selling something?’ And I said, ‘I'm trying to meet managers. I'm trying to build relationships with the places that I'm going to be selling at. I can't immediately start selling. It's a brand new brewery’.

“So that was one of those things that just kind of put me off a little bit at the beginning. And it was a small investor too; I think he put in like 50 pounds or something. I was like, ‘Why are you putting something negative on the Facebook page?’”

There is plenty he would change if he could do it again, he says. He would take his time, offer a less eye-popping deal to investors. “I learned a lot,” he says. “But at the same time, I can count on one hand times I actually was elated about what I had done. To start your own company, it's not for everyone. It definitely taught me to respect other entrepreneurs, whether they've failed or whether they've succeeded because they've all gone through similar experiences. So I'm glad I went through it, I learned a lot, but it took years off my life.”

It's no surprise he hasn't brewed since. The kit was sold “to a couple of guys in Liverpool - we did the deal and I never looked back,” the lease in Leyton elapsed. But some good came out of it, too. He has fond memories of other London brewers (“Every single brewer I met was super helpful. They really gave encouragement, gave advice”) - and that high-school friend, Ken Graham, now has a thriving business in the capital, Sodafolk: “I think Brüpond helped him get a lay of the land of London.”

Brassfield now works for SystemsAccountants, a London-based company, which could see him back in the British capital now and then for work. It’ll give him a chance to get reacquainted with a beer scene that has changed hugely in the past half-decade. “It’s great to see what’s happened,” he says.

The Brüpond blueprint has become the norm in London’s brewing culture: crowd-fund cash, find a site on an industrial estate, push the brand hard on social media. It didn’t work out for Brassfield, but plenty of others have followed in his footsteps. Not that he’s feeling jealous. As our conversation ends, I ask him if he would ever consider going back into brewing? “No, I don’t think so.”