Why Liverpool’s pubs are so fascinating

It’s a foul evening in Liverpool. Every 20 minutes or so the skies open, soaking Hope Street in icy rain, sending young and old scurrying for cover. At The Philharmonic Dining Rooms, the Gin Palace par excellence and Liverpool’s most famous pub, the heavy wooden door opens and shuts, opens and shuts, opens and shuts, as bedraggled customers jostle into the warmth and light.

Many of these pubgoers are not here primarily to get out of the rain, though. From my perch close to the bar, a pattern soon emerges. A group enters and stands, a touch bashfully, close to but not at the bar; one member goes to the bar; s/he mentions a booking; they’re led into the Grand Lounge, a richly ornate former Billiards Room that is - in the evening, at least - now devoted to eating.

None of them have Liverpool accents; they’ve all travelled here, like me, to see the shiniest jewel in the city’s pub crown. You might think it’s a shame that such a place is used mainly by tourists - but actually, The Philharmonic, opened in 1900, wasn’t built for ordinary Scousers. As Quentin Hughes put it in his marvellous 1964 architectural guide to the city, Seaport, “Buildings like this … formed part of the [mercantile] culture [of Liverpool], a setting to which wealthy businessmen had become accustomed.”

It’s easy to forget that Liverpool was once like that, a place where a barbed quip from its rival city, “Manchester Man, Liverpool Gentleman”, made sense. Both Liverpudlians and outsiders have done their best to forget the era when Liverpool (or at least its merchant class) was hugely rich, when it was Tory, when sectarian division was as much a part of the culture as it has been down the years in Belfast and Glasgow.

You sometimes hear people describe Liverpool as an Irish city, and a walk around the centre shows why. There are dozens of pseudo-Irish boozers, all Emerald Green and exhortations to enjoy the craic. The Celtic Corner. The Blarney Stone. McCooley’s. It seems unlikely that anywhere loves Ireland more than modern Liverpool (I haven’t been to Boston, admittedly).

But to have called Liverpool ‘Irish’ when The Philharmonic first opened would have been to risk a full-blown riot. Liverpool once had a sectarian divide as wide as anywhere, a divide that persisted well in the post-War period, a divide that was a key part of the city The Beatles grew up in. (Neatly, The Beatles’ religious upbringings were perfectly balanced: Harrison - Catholic; Lennon - CofE; McCartney - agnostic; Starr - evangelical).

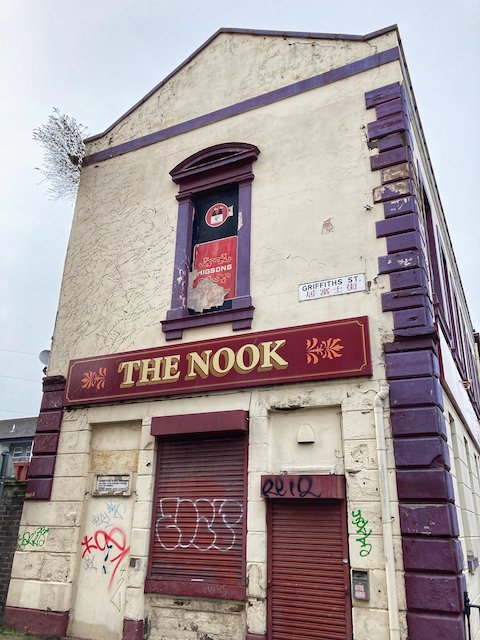

Liverpool has outgrown that, but not just that. To a degree, sadly, it also seems to have outgrown pubs - or at least, a certain type of neighbourhood pub. In Chinatown, there’s a small tree growing out of the long-closed Nook, where last orders were once called in English and Cantonese. In L8 (Toxteth or Dingle? No idea), a short walk south, The Globe is the last pub standing on a street which once had many.

To the East, on Smithdown Road, is The Royal Hotel, once a key part of the city’s famous student pub crawl, now home to student flats. Apparently it was gas-lit into the 1990s; only the marvellous tiled exterior survives now. Many of the other pubs on the crawl are also shut.

Indeed, during a three-hour walk through this charismatic chunk of south Liverpool, only the pubs on bourgeois Lark Lane - coffee, boutiques, murals, etc - seem to be thriving. Elsewhere they’re increasingly scarce. In that respect, though, Liverpool is like the rest of England, where an abundance of choice has replaced the one-size-fits-all Local (where, needless to say, not everyone fitted).

All the displaced pub energy here seems to be focused on the centre. Britain’s city centres have been increasingly drink-focused since the 1990s, but few are as lively as Liverpool. There are boozers of all kinds, from The Philharmonic all the way down to a bar devoted, rather perversely, to Only Fools and Horses. Bold Street has got all the casual dining you might ever need.

There’s a feeling of restless change - epitomised by the new Everton football stadium, emerging from Bramley Moore dock to the north of the centre - a feeling reflected in these drinking options: a big glass-fronted Yates is five minutes’ walk from its more restrained predecessor, now forlorn behind metal grill fencing.

Liverpool’s centre offers a mixture of evolution and conservation that should keep everyone happy. There are many beautiful and inviting pubs, even if the otherwise excellent Museum of Liverpool doesn’t (as far as I could see) touch on their role in the city’s story. My favourites are the Roscoe Head, a haven of interwar cosiness, pies and warm welcomes, and The Lion Tavern, with its tiled corridor and ‘News Room’, which may actually be the acme of pub comfort.

If the Museum ever decides to add something about drinking in Liverpool, I’d suggest a recreation of the American Bar in Lime Street (“probably the most famous hostelry in Great Britain, behind London’s Cheshire Cheese”, according to The Liverpool Echo when it shut in 1930), which was the first port of call for arriving Yanks and theatrical stars in the first years of the 20th century. It was run by Mary Ellen Egerton, ‘Ma Egerton’, an Irishwoman, whose next move was to take on The Eagle Hotel behind Lime Street Station, the pub which still bears her name.

On that same sodden Tuesday evening, I ended up there, watching the last knockings of Manchester City’s evisceration of Red Bull Leipzig, chatting to a local couple about this and that. A perfect pub moment, a timeless joy in a city where forgetfulness and memory walk hand in hand.

Enjoyed this but thought there wasn’t enough about London? Sign up to my monthly newsletter about London beer & pubs, London Beer City